An Introduction to Ruby classes and objects

When you start learning Ruby, you often hear that everything is - or evaluates as - an object. And you’re usually like “🤔 Come again”?

Objects are the main paradigm in defining Ruby as a language. Objects and classes serve as blueprint. But when objects are defined by other objects, the recursion can seem a tad difficult to grasp at first.

So, here’s an introduction to objects and classes in Ruby for my fellow Ruby developers out there.

What is an object?

An object is a piece - any piece - of data (regardless of the language you're using). That's it.

Some types of data:

'Hey there'is a string.1is an integer.5is another integer.👶is a baby.[]is an empty array.

Easy right?

Ruby’s Objects and classes 101

Now, to handle objects, Ruby creates a set of abstractions handling common behaviors for the same objects: classes.

Let’s dive in:

1 and 5 are different integers, hence different objects.

But 1 and 5 are both integers, so Ruby assign them the same class - the Integer class.

The Integer class holds a specific set of methods every integer can call. Developers can then expect common patterns for different objects described by the same class.

# For instance, the + method is defined in the Integer class.

# It instantiates and returns a new integer summing the previous ones.

1 + 5 # => 6Let’s call the method .class on some objects to check their Ruby class.

'Hello there'.class # => String

[1, 2, 3].class # => Array

true.class # => TrueClass

# It even works with your own classes

Wood = Struct.new(:species)

Wood.new('mapple').class # => WoodClasses as blueprints

Classes act as blueprints: you define which data they need and what they can do with it. Then, you can create as many instances - think of instances as casts shaped from a mold - from the same blueprint.

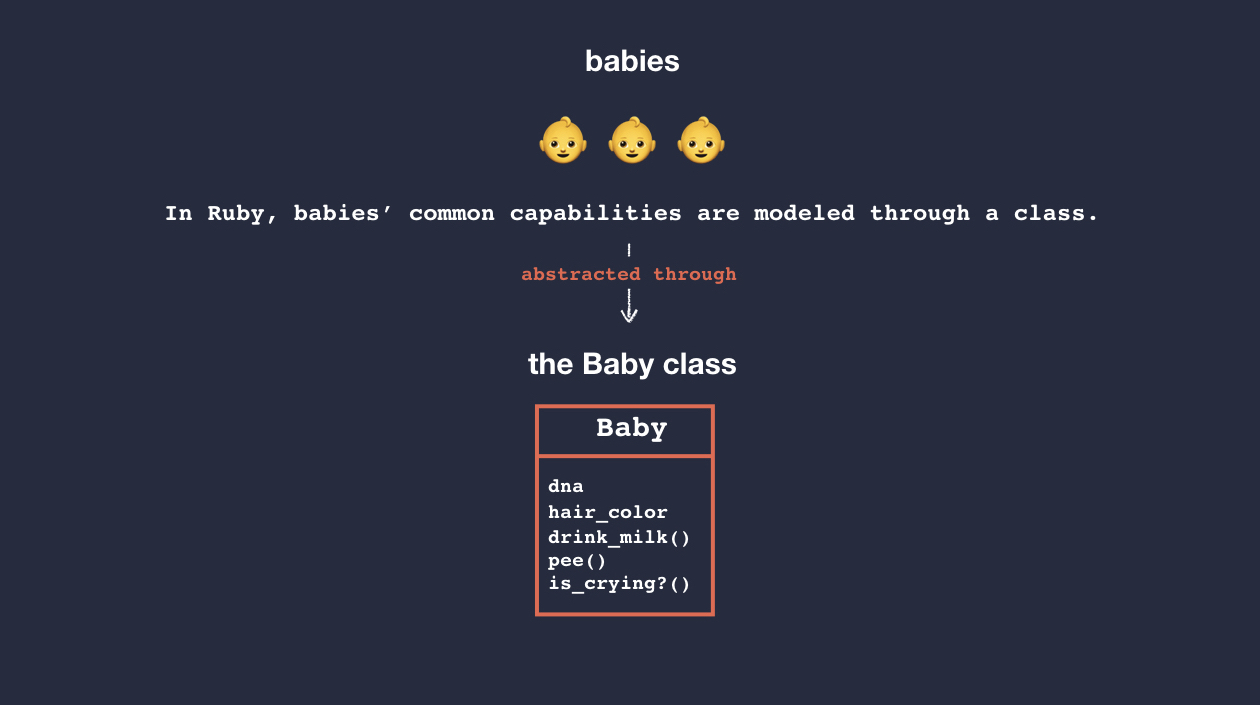

Let’s create a blueprint for babies. Here’s what our Baby class needs:

- Some data to begin with: a DNA hash should do the trick.

- Some basics behaviours and capabilities.

class Baby

# accessor

attr_reader :dna, :hair_color

# constructor

def initialize(dna)

@dna = dna

@hair_color = @dna[:possible_hair_colors].sample

@hungry = true

@dirty = false

end

# behavior

def drink_milk

@hungry = false

end

def pee

@dirty = true

end

def is_crying?

@hungry || @dirty

end

endHere, I now have a blueprint for babies. It’s pretty limited but here’s what it does:

- When new babies are conceived, they receive a mix of information - their DNA -, and they’re both hungry and clean.

- In utero, babies will sample the DNA and “pick” a hair color.

- Once they’re born, babies can drink milk and not be hungry for a while, or pee themselves and get dirty.

- If babies get hungry or dirty, they cry to see their need met.

A baby is an “object” whose information and behaviors are specified by a class. Different babies are different “objects” but they all share the same set of basic capabilities.

Let’s recap:

So far, we have objects categorized by classes and, whose common information types and behaviors are defined by methods.

Objects as Object (a.k.a, the mindfuck)

Yes, I know, it seems like I’m in for the tautology of the year. And yet, different objects can have common behaviors too!

Let’s take an example with the method inspect which returns a human-readable representation of the object. We’ll make a new baby 1 and print her information in my console.

baby = Baby.new({possible_hair_colors: ['brownish', 'pale blonde', 'a pinch of redhead']})

baby.inspect

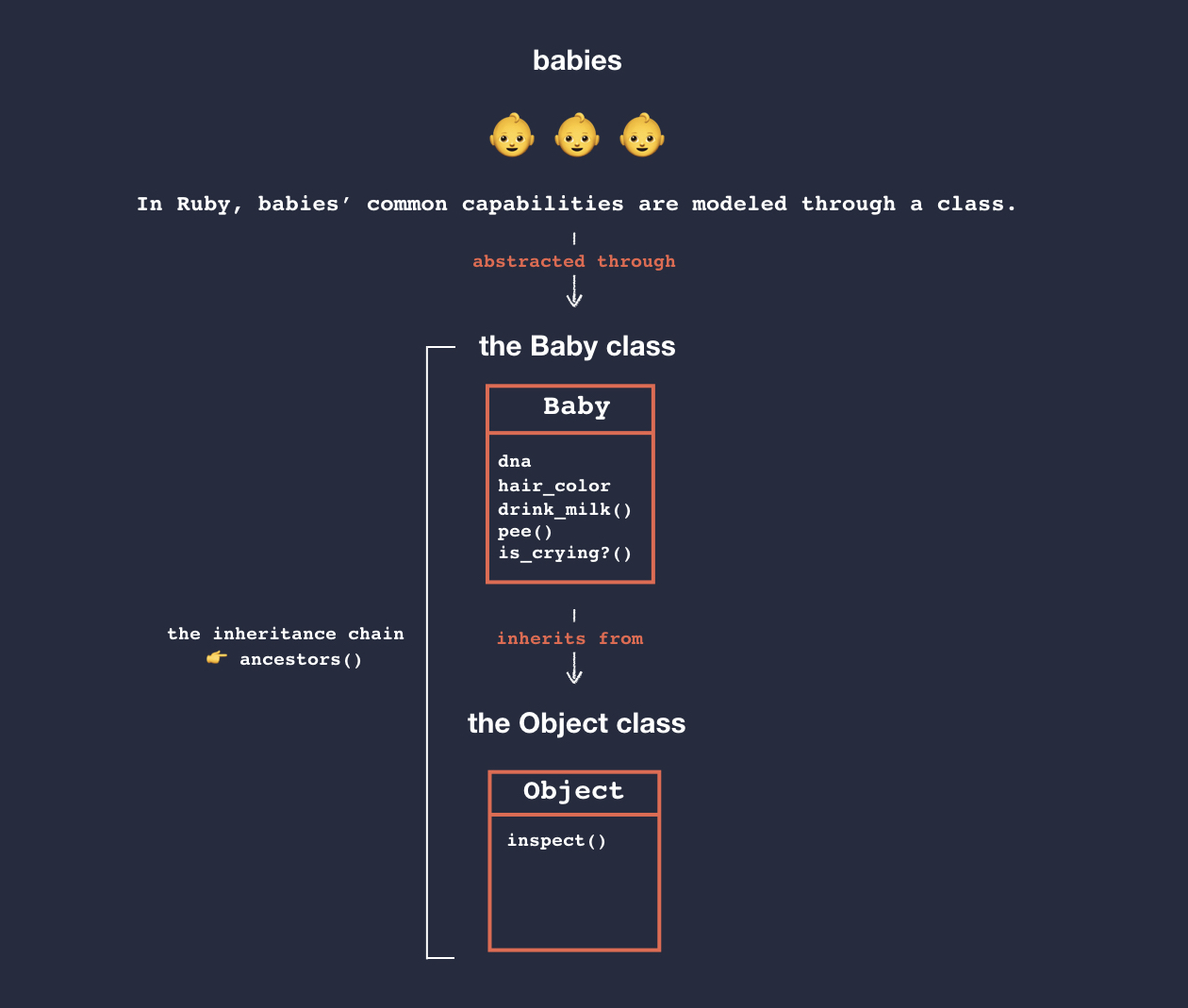

"#<Baby:0x00007ff2934b3150 @dirty=false, @hungry=true>"But how can inspect returns anything at all since it’s not defined in my Baby class? If it’s not defined in Baby then, where is it?

To find out and pull on the thread, let’s get back to our console.

self.inspect # => "main"

self.class.inspect # => "Object"

Object.public_methods.include? :inspect # => trueWhat have I just done? I’ve inspected the current context - self - in which I am when I open my console. The current context is the main object. And in Ruby, the main object is represented by the class Object. Still with me?

Forget about Ruby and web development for a second. Consider this main object as the mother of all objects. Every object is unique, yet they all share common patterns. For instance, they can be inspected, analyzed, etc. You can inspect integers, trees, strings, and babies all the same. Nothing stops you to submit any object to your scrutiny.

Well, that’s the same in Ruby. Any object can be inspected. It’s a common behavior shared by all objects. And this behavior is defined in the Object class with the method #inspect as you can see in the third line of the console screen above.

Object is the default root of all Ruby objects. [...] Methods on Object are available to all classes unless explicitly overridden. The Ruby doc

It allows Ruby to define methods at appropriate levels of abstraction.

You can dig deeper and check the full inheritance chain by running Object.ancestors in your console. For those who want the TL;DR, Object inherits from BasicObject and mixes in Kernel’s methods (like the p method, we junior developers use everywhere to debug our code).

Let’s sum everything we’ve seen so far:

Objects are pieces of data. Different objects can relate to the same class. Classes receive and handle data in their specific way. All classes inherit from the `Object` class and its methods.

Haven’t lost you yet, have I? Good! Then, let’s talk about the object that describes all classes: the class object and its Class class.

Still there? 😅

The Class class

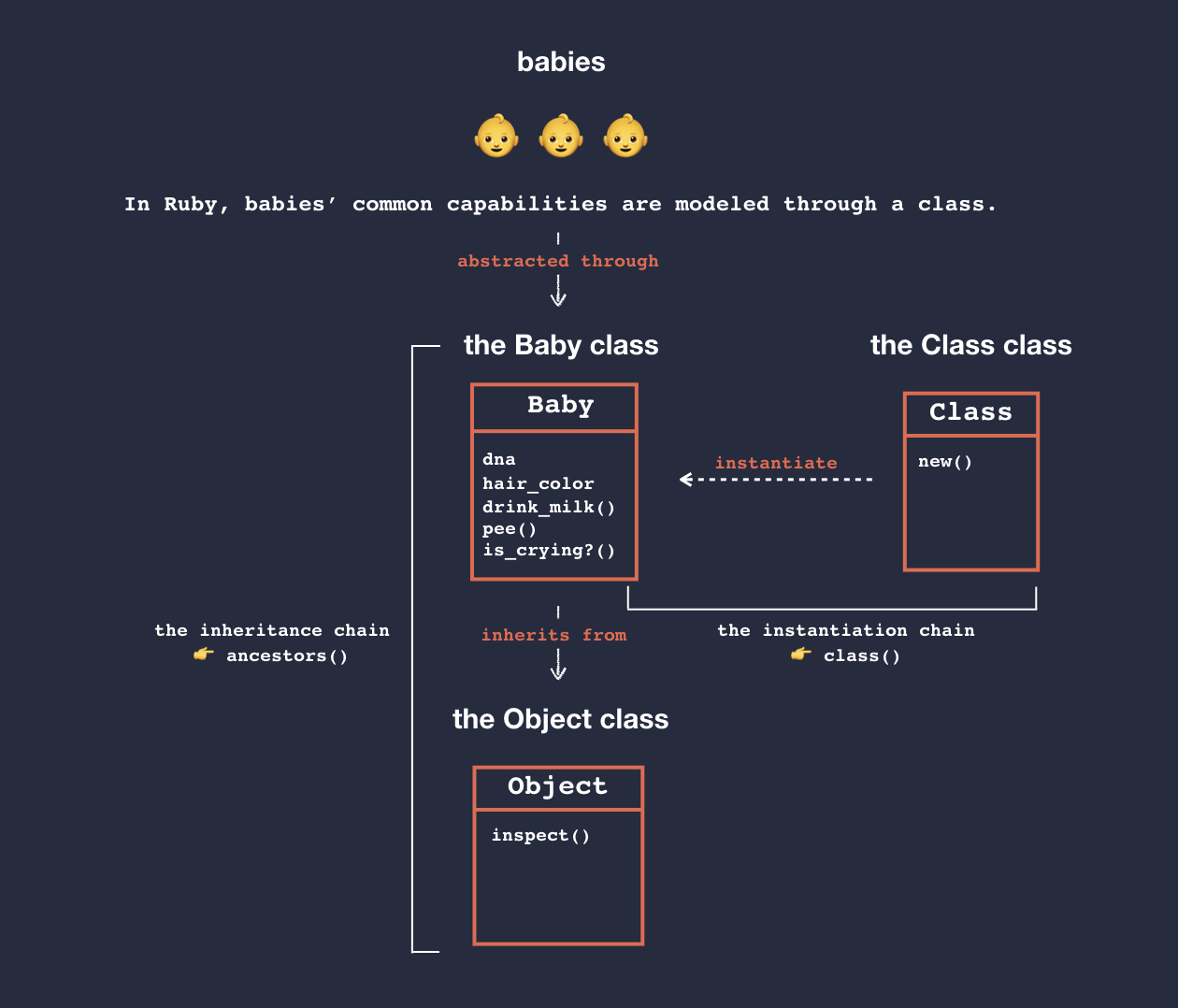

When you think about it, classes are nothing more than objects. If 'Hello there' is a string and 1 is an integer, String is a class (i.e. a blueprint). So as an object, Ruby has given it its own class: the Class class.

Class inherits from Object but also defines some pretty common methods. Let’s see:

Class.public_methods.include? :new # => trueEvery time you’re calling #new on a class you want to instantiate, you’re using an instance method of the Class class. Wait, what? If `#new` is an instance method of `Class` and if I can call it on my own `Baby` class too, it means that all classes are instances of the `Class` class?

That’s right my friend!

As an instance method of Class, #new is accessible by all instances of Class like our Baby class.

My Baby class does not have a #new method. And yet, I can create new babies with Baby.new(dna). It’s because all classes - String, Integer, Baby, etc - inherit from Class.

Let me show you how it works when you define a class in your code.

Writing :

class Baby

# some stuff

end

baby = Baby.newis the same as:

Baby = Class.new

baby = Baby.newSo if Baby and Class are both classes, they’re both instances of the Class class? Yep. Class.class returns Class. It’s recursive.

Let’s wrap up before letting you massage away that headache of yours:

Objects are pieces of data. Different objects can relate to the same class. Classes then receive and handle data in their specific way. All classes inherit from the `Object` class and its methods. Classes share common behaviors defined in the `Class` class.

I hope you enjoyed the ride as much as I did!

Keep in mind that this is only an introduction. There are many broad strokes and many (more or less voluntary) omissions on my part. If you enjoyed the topic, check out the rest of my essays on Ruby.

Many thanks to Nicolas and Sylvain for reading my drafts, asking a lot of questions, and making this introduction to objects and classes (much much) better.

Noticed something? Ping me on Twitter or create an issue on GitHub.

Cheers,

Rémi

-

My upcoming post “How to make babies in 30 seconds thanks to Ruby”, soon in your RSS feed. ↩