From stained-glass master to software engineer: it starts with a mess

I often tell the story of how I became a software engineer.

What I love about this story is that it always starts with an outrageous lie:

I’ve had a pretty straightforward trajectory.

As you might realize now, I firmly believe that facts shouldn’t spoil a good story.

The reality is more mundane (and does not fit in a 30-minute interview). But now that I’m entering my fourth year as a software engineer, I can tell you the real (hi)story.

And as stories go, it starts with a pretty damn mess.

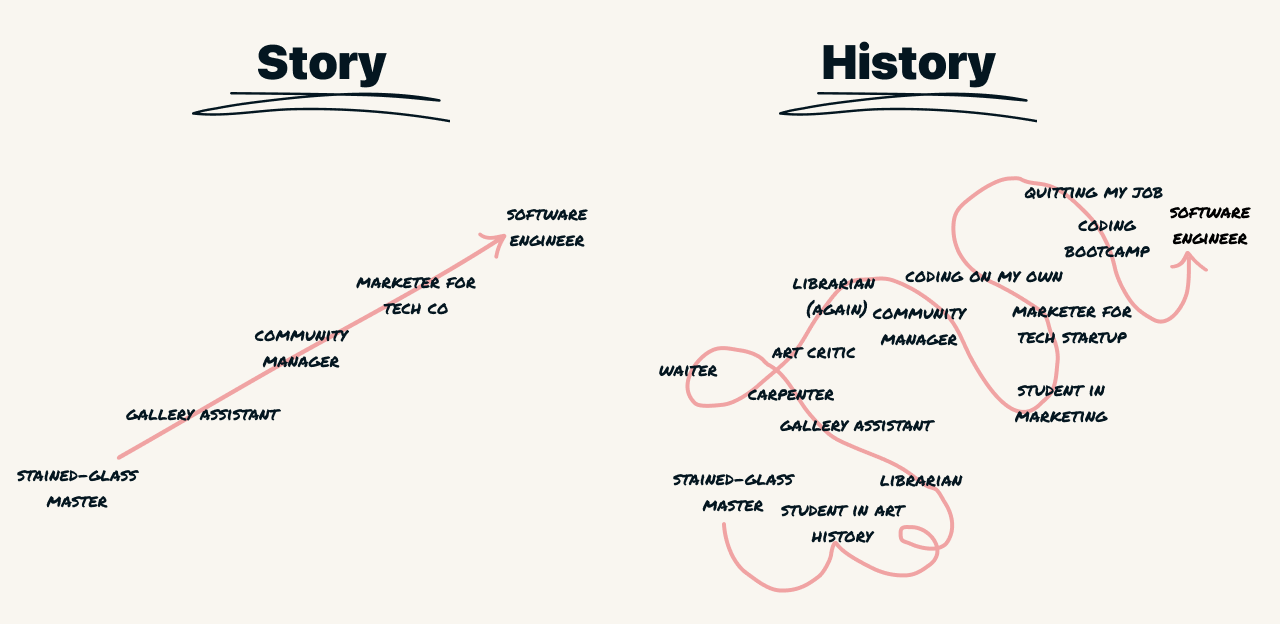

Good stories are linear.

First, let me tell you how I pitch my professional background.

I’ve had a pretty straightforward trajectory.

In 2004, I started working as an apprentice in a stained-glass workshop. For four years, I’ve restored stained glass in French churches.

Then, in 2007, I quit my job to learn museology at the Ecole du Louvre. From 2007 to 2011, I worked in museums and art galleries. But in 2011, while working for a London gallery specializing in emerging artists, I started creating content for their social media accounts.

This was when I realized I liked working on the internet more than with artists.

In 2012, I was already making a good living in marketing. I already had clients in France and the UK. I was creating content, managing social media accounts, creating websites, etc… My expertise landed me a proposal to work with an open data startup. They had a very technical product and didn’t know how to present it to non-technical people. Until 2018, I spearheaded their lead generation and inbound marketing strategies, resulting in more than $600,000 ARR.

Near the end of my stint, I realized I was spending more time with the technical team than the marketing one. I wanted to have an impact on the product, not just make it look pretty as an afterthought. After badgering my developer friends to learn the basics, I decided to step up my skills through a coding bootcamp.

Three weeks in, I knew I would never get back. I was hooked. I had found my magic.

I got my first job right after the bootcamp, focused on creating maximum value for my team, and the rest is history.

I am very proud of this story. It’s linear to a fault, but it works and I can tell it under 2 minutes. It’s a perfect pitch for interviews.

All the facts are true. The linearity is not.

Artists, companies, and people do this all the time. They select facts in their history and bundle them up in a nice crisp story. If you’re someone with an unregular background, why not take a leaf out of their book?

But real life is a mess.

The history - not the story - of my becoming a developer sounds more like a 10-year-long stream of consciousness:

- art history, then museology student

- librarian in various museums

- multitasking free labor in galleries

- freelance carpenter (although I had never worked with wood before)

- waiter

- community manager

- freelance art critic

- back to being a librarian to pay the bills

- freelance content marketer

- marketing apprentice in a startup

- first scripts in Excel and Javascript to clean some data

- fulltime inbound marketer

- getting the basics of programming objects and relational databases

- quitting my marketing job and learning Rails through a coding bootcamp

- teaching basics of Ruby to new students at said bootcamp

- coding apps to level up my technical skills

- finding the first job after +30 interviews

My history is a succession of doubts, weird changes, veering off paths, circling back, being stuck in boring jobs, etc. There’s no linearity. It’s hard to explain, and it’s hard to grasp.

Does it make me a lesser professional? Not at all. I know these experiences give me an uncanny number of edges in my day-to-day practice.

Once, my team asked me to draw a proposal for a classification for error codes for technical and non-technical people. Thanks to my time as a librarian, I was able to propose a first draft based on enumerative and faceted library classifications 1.

Marketing has helped me promote my work, get better opportunities, and make complex topics more understandable to people.

All these experiences are valid. But to make other people see them as such, I learned I had to share them in a timely manner.

That’s why I select the most relevant experiences and create a story that people can grasp in two minutes. Because where I come from is not that important. It’s just a way for people to validate that I’m not a complete fluke. A linear story is a story quickly out of the way. It leaves room for more relevant topics like your technical abilities, people skills, and achievements.

Thinking change is possible takes time.

Changing careers is not easy. It’s a process that can take years. Years of doubts: “Am I smart enough to code?”. Years of questions: “Where am I going to find the time to learn?”. Years of not knowing if you’re making the right choices: “Should I learn on my own, go back to university or do a bootcamp?”.

It’s taken me years to accept that coding might be a good choice for me. I never had a love for computers. I didn’t spend my childhood building compilers. I did not fit the archetype of the "Real Developer™" so it was hard to picture myself as one.

Sometimes, a change hides within a previous change.

When I started working in content marketing for an open data startup, I could not realize that I would get pulled toward building products so strongly.

I guess my message is: it’s okay if you feel like changing careers takes forever.

You might need this time to cut your losses and accept that your academic degree or current career path is not a good fit. I think it speaks more about how society herds people into a limited number of professional paths rather than some faults of your own.

Upon finishing my Master’s degree in museology, I knew it was not a good fit. I had worked in a few museums and realized I had zero interest in pursuing a career as a curator or an art critic. I tried anyway because I had invested time, money, and effort into this path. I needed time and a handful of disappointments to accept what I already knew.

Same story for marketing. After two years, I knew I’d grow bored with promoting half-baked products. I wanted to have more impact on software. That’s what I love to do. I love to create stuff, to make things. But to be able to make that move, I needed a few years to steer the ship in the right direction.

Change requires organization and support.

Something often overlooked in our individualistic society is how support is crucial to nail a career change.

When I decided to learn through a coding bootcamp, the first thing I did was to get my family on board.

Le Wagon requires a two-month full-time commitment. Sessions start at 9 am and until 7 pm. Evenings can fill up pretty quickly with late coding sessions, job fairs, talks from founders, etc. And when you have a family, you can’t do that without getting an agreement first (at least, I wouldn’t).

Finding money was another subject that required time and organization. To pay for my tuition, I kept my marketing job for almost a year - even when I desperately wanted to quit - to stash up some money. I also negotiated a loan to pay for the bulk of my training. In France, people can be eligible to get monthly allowances when unemployed. But to get it, I needed to conduct successful negotiations with the company I was working for. And I could not have done this without the support from my family, friends and strangers.

Testing the waters is also a good idea before committing to an all-in change. I tried coding static websites, MOOCs, online courses, and small-scoped side projects. But I wasn’t sure until I had spent three weeks coding fulltime at the bootcamp.

Here, I can’t be thankful enough to the people who helped me in this crucial (and fragile) moment.

Without support, I’m not sure I’d have taken the plunge.

Hope you liked this (hi)story as much as I liked writing it!

Cheers,

Rémi - @remi@ruby.social

-

Enumeration allows for a basic domain-based classification to be set up:

500 Natural sciences and mathematics > 510 Mathematics > 516 Geometry. Facets give flexibility and evolutivity to enumeration:516 Geometry > 516.3 Analytic geometries > 516.37 Metric differential geometries > 516.375 Finsler geometry↩